I stared at the wall, hoping solutions would appear. Solutions failed to appear. I stared some more. Solutions persisted in their absence.

The job was supposed to be relatively straightforward. My boss at the Corps had a hive that had shown up at his house, and had taken up occupancy as unwanted guests. He had asked me to go and take a look. I looked. The house had shiplap siding, and the bees were coming and going in an interior corner in the building.

I looked under the house in the crawlspace, and there was no evidence that the bees had any access to the space under the house. No sound, no motion, no dead bees at the entrance.

And no comb to be seen anywhere.

- Remove shiplap siding, cutting away just enough to expose the comb,

- Remove the comb, brushing away bees into prepared boxes,

- Place any recently laid brood comb in the boxes,

- Vacuum any remaining bees,

- Clean up,

- Claim my check.

It was a hot day, but the work should be pretty easy. My only concern was how to minimize the damage to the siding. "This appears to be a pretty straightforward job," were the words that came out of my mouth.

I arrived on Sunday afternoon, all smiles and selfies.

|

| Happy beekeeper. It would not last. |

First step: remove shiplap siding. Since I had not actually tried to remove any of the siding before I got the contract signed (it is considered bad form, apparently, to start demo before you get approval), I was worried that the siding was HardiePlank - the concrete siding. If so, I was in for a rough go of it on the demo. That stuff is tough to cut.

Turns out, it was the masonite variety - much easier to break/remove/cut. I breathed a premature sigh of relief.

And got to work. First obstacle was the presence of a moisture barrier (easily dealt with) and a layer of waferboard (OSB) under the siding. Not completely unexpected, but it made the job a little tougher. So instead of just prying the boards loose, I was going to have to cut them out.

Reciprocating saw to the rescue!

After I had cut deeper than I had thought was necessary, I pried up a section of the OSB, and found wood underneath. I cut a wider swath through the OSB, and uncovered more wood. And then more.

And more.

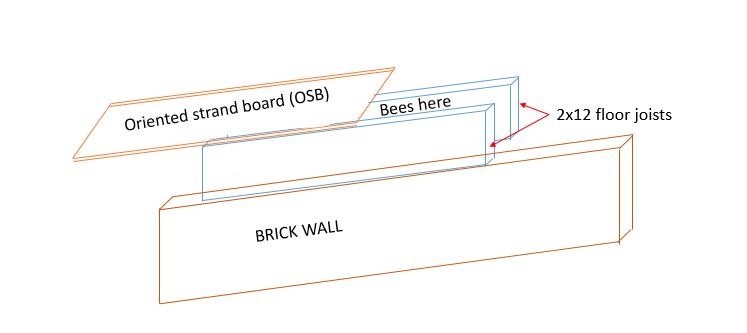

Finally, I had pried and cut and uncovered as much as I possibly could. I was staring at a 2x12 pine board - a floor joist that bore the weight of the house on it.

That's right. A load-bearing floor joist. Not the thing you want to cut. Bees were just on the other side of it. And on top of the pine boards was the subflooring - another layer of OSB. Immediately on top of that was the wall studs.

|

| Rough diagram of the Cutaway of the corner |

I now had a full inventory of what was there. What I did not have, apparently, was a way in.

Can't cut away the brick. Can't cut away the load-bearing joist. Can't cut away the subfloor that the wall sits atop. Cutting the wall does not do any good - it won't get me into the void.

I sat on my bucket, wondering why I had decided that this was a good way to make some extra money.

And here we join again where we started the blog entry. I stared at the wall, hoping solutions would appear. Solutions failed to appear. I stared some more. Solutions persisted in their absence.

I went back under the house, intent on doing more than just a spot check. Sure enough, there was a tiny, two-inch crack between the joist and the brick. Maybe enough to get my hand between the boards. And in that crack, there be bees - bright, beautiful comb clearly visible.

As I backed out of the crawlspace under the house, my hand rested on something papery. My flashlight identified it as an 8-foot snakeskin.

Now, friends, my option is to go under the house, sharing tight quarters with what might be a snake, focusing on the removal of bees from a remote location where I only have a 2" access crack, on a 95-degree, 100% humidity day in August. Or I could go home and drink cheap beer.

Beer never sounded so good.

With a lot of grunting and maybe some swearwords, I folded myself into the space and started cutting out the comb. After the second piece of comb, the nectar and honey began to flow downward. Onto me. I got coated in dripping honey and nectar for the next hour, and then needed a break.

I shared the wealth with the Bodrons, who looked suspiciously at the pieces of honeycomb with bees still attached. "How do you eat it?" A couple of bites of pure, unadulterated honeycomb later, and they both were convinced that fresh honey was something special.

"One thing to know", I explained. "This is not honey. It is only honey after it gets to a certain humidity level, and we stopped the bees from getting there. As it is, it will ferment, so you will need to screen it and keep it in the fridge - it simply won't last very long."

One sip of water later, it was time to go back in. I cut away more comb, finally beginning to see brood comb. There was absolutely no way to keep the comb intact, because it all had to be compressed (read: squished) to get it out of the gap between the board and the brick.

Another hour later, and I am dripping honey from every spot on me. I finish up the cutting out of the comb, and brush the cluster of bees into a bucket, before hauling them out and transferring them into a box that is waiting on them.

Each time I come out of the crawlspace, it gets harder to convince myself to go back in. But several more trips, and I have cleaned the areas out as well as I can, I have dosed the area liberally with poison to discourage the bees from coming back, and I have sealed up as much as I can with expanding foam sealer. I have vacuumed up, cleaned up, and treated as much as I can.

I slide myself out from under the house, gather up the stuff I need, and trudge to the truck.

It ends up taking two more trips out to complete the tasks associated with the removal, and every time I get in my truck I find a new spot that has honey residue still sticking around.

But the bees have been deposited in their new home, and were last seen happily buzzing around all of the nectar-honey that I had fed back to them. Hopefully making a new home where they were wanted.

And I headed for that beer. Straightforwards.